Enhanced technologies, new industrial possibilities and not only the change of a century, but also of a society. And while societies are collectives, it is the people who make up said societies.

The journal articles in this week’s material deal not only with the Western Canada labour revolts, but in a way also address the issue of individualism which is what I believe to be one connecting factor between Conley’s and Belisle’s articles.

In order to understand different takes on interpretations of Western Canadian labour history, Belisle points out the importance of conducting a structural comparison between “frontier labourers, craftsmen, factory operatives, and settled urban workers” (Belisle 2003). But what combined each of these groups was the way they used collective action and broader organisation of themselves to strike for political objectives, especially in the later strike waves around the time of the First World War, although a sense of a new form of collective action can already be discovered in 1903, when sympathetic strikes were tried in support of one branch of industrialism, one of the most prominent cases being the Vancouver Trades and Labor Council (VTLC) striking in support for United Brotherhood of Railway Employees (UBRE). The following provincial election in 1903 showed that workers in Vancouver were “favourable to new political goals” (Belisle 2003), seeing the numbers for the socialist and labour vote.

From individuals who produce for the masses who consume -and what consumption could mean for individuals- is where Conley’s article could be heading. More specifically, she draws the connection between consumption and individualism as the first being one sort of self-expressionism: “As well, activities such as “lifestyle shopping” have enabled individuals to become not only possessors of various items that reflect their personalities but also possessors of various styles of items that reflect their personalities” (Conley 1989). This is especially interesting if one considers that the very idea of mass-producing should defy any sense of individualism, which is something Conley mentions herself before acknowledging that “self-expression through commodity-consumption is at once individualizing and homogenizing” (Conley 1989). One could debate if political power, as a logical consequence, demands this sort of double-character of individualism and collectivism, but this is something that this week’s reading material can’t cover on its own and may need some more in-depth research.

In a sense, this can also be applied to the idea of individualism and collective measures to provide political influence I mentioned in the earlier paragraphs of this entry when talking about Belisle’s article. With their own specialties threatened by new developments, Western Canadian workers needed to overcome their differences, and therefore in a away also what made them great, to form collectives.

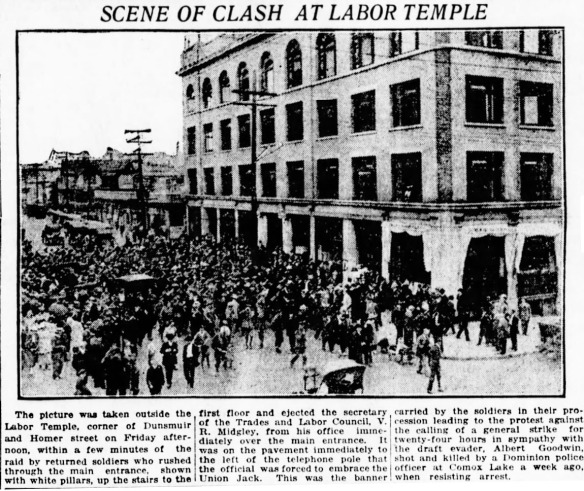

And in some cases, it could even lead to collective answers on individual tragedies such as the General Strike in 1918 which followed the death of Ginger Goodwin -and which dimensions are visible in the following picture captivating the attack of soldiers on the Vancouver Labor Temple which is taken from the Vancouver Daily World that published it on August 3, 1918:

References:

Belisle, “Toward a Canadian Consumer History,” Labour/Le Travail, 52 (Fall 2003): 181-206.

Conley, “Frontier Labourers, Crafts in Crisis and the Western Canada Labour Revolt: The Case of

Vancouver, 1900-1919,” Labour/Le Travail, 23 (Spring, 1989): 9-37.

https://pasttensevancouver.wordpress.com/tag/labor-temple/